The State of Biodiversity in 2026: A Poet’s Reckoning With a Planet in Crisis

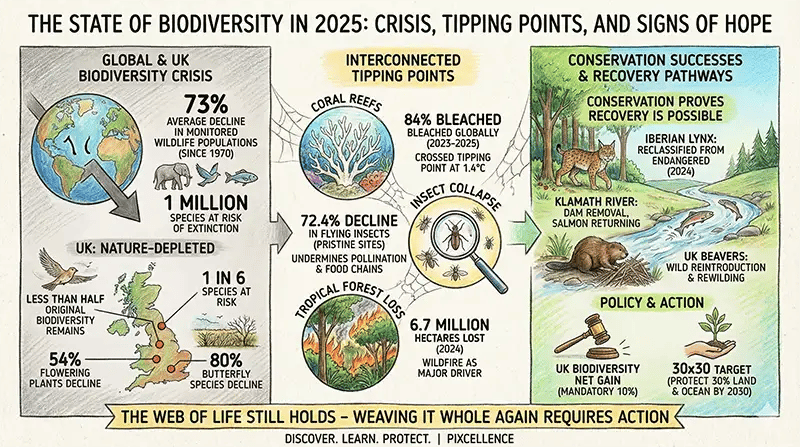

Global biodiversity is in severe crisis. Monitored wildlife populations have declined by 73% since 1970, approximately one million species face extinction, and 84% of coral reefs have bleached in the worst event on record. Pixcellence’s analysis of 2024–2025 research from the WWF, IPBES, and IUCN reveals a planet at a tipping point — yet conservation successes prove recovery remains possible.

There is a tradition in English poetry, stretching from William Blake through to Ted Hughes and Alice Oswald, that insists the natural world is not merely scenery but moral witness. When Blake wrote that a robin caged puts all of Heaven in a rage, he was articulating what ecologists now confirm with data: every act of destruction ripples outward through systems we barely understand.

This article examines the state of global and UK biodiversity through that dual lens — the poet’s reverence and the scientist’s precision — because the crisis demands both. The numbers alone are staggering. But numbers without feeling produce paralysis. And feeling without evidence produces sentimentality. What follows is neither.

In This Article

- How Severe Is the Global Biodiversity Crisis?

- The UK: One of the Most Nature-Depleted Countries

- Coral Reefs, Insect Collapse, and Tipping Points

- Species We Lost in 2024–2025

- The Sixth Mass Extinction Debate

- Conservation Successes That Prove Recovery Is Possible

- COP16, Biodiversity Net Gain, and the Policy Landscape

- Why Poetry Matters in a Crisis of Numbers

- What Can Individuals Do to Help?

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Severe Is the Global Biodiversity Crisis in 2025?

The global biodiversity crisis has reached a severity that the scientific community increasingly describes as existential. The WWF Living Planet Report 2024, released in October 2024 and tracking nearly 35,000 population trends across 5,495 vertebrate species, found that monitored wildlife populations have declined by 73% on average since 1970. That figure is not a projection or a model — it is a measured collapse within a single human lifetime.

Freshwater species have suffered most severely, experiencing an 85% population decline, followed by terrestrial species at 69% and marine species at 56%. Latin America and the Caribbean have experienced a 95% decline — near-total ecosystem collapse across an entire continent. The IPBES Global Assessment estimates approximately one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades, with current extinction rates running tens to hundreds of times higher than the natural background rate over the past 10 million years.

These are not abstract numbers. They represent the emptying of rivers, the silencing of forests, the bleaching of seas. As Pixcellence has documented across its biodiversity crisis resource hub, this is not a future threat — it is a present emergency unfolding in real time across every continent and ocean.

73%

Average decline in monitored wildlife populations since 1970, based on nearly 35,000 population trends across 5,495 vertebrate species. — WWF Living Planet Report 2024

The UK: One of the Most Nature-Depleted Countries on Earth

The United Kingdom now ranks among the most nature-depleted countries on the planet, retaining less than half of its original biodiversity. The UK State of Nature Report 2023 — a collaboration of more than 60 conservation organisations — found that one in six of Britain’s 10,000+ assessed species is at risk of being lost entirely, with an average 19% decline in species abundance since 1970.

The details paint an even more troubling picture. Some 54% of flowering plant species have declined in distribution since the 1950s. Moths have declined 31% since 1968. Seabird populations have fallen 24% since 1986. An alarming 80% of UK butterfly species have experienced declines since the 1970s. Bumblebee Conservation Trust data from 2024 confirmed it was the worst year for bumblebees since records began, with average declines of 22.5% across 24 monitored species.

For educators and conservationists working with Pixcellence’s biodiversity loss resources, these figures transform abstract global statistics into a local reality visible in any British hedgerow, meadow, or garden. The skylark that once defined the English countryside is disappearing from the skies above it.

Coral Reefs, Insect Collapse, and the Tipping Points Scientists Fear Most

Three interconnected crises illustrate how biodiversity loss cascades through Earth’s systems. The fourth global coral bleaching event (2023–2025) — the most extensive ever recorded — has affected approximately 84% of the world’s reef ecosystems across 82 countries, according to the International Coral Reef Initiative. NOAA was forced to add three new alert levels to its bleaching scale to capture the severity. The Global Tipping Points Report 2025, authored by 160 scientists, declared that warm-water coral reefs have already crossed their tipping point at current 1.4°C of warming. Live coral cover has halved since the 1950s.

The insect crisis, often called the “insect apocalypse,” is equally alarming. A 2025 study from UNC Chapel Hill, published in the journal Science, measured a 72.4% decline in flying insect density over 20 years at a pristine mountain site in Colorado with no direct human activity — implicating climate change as a driver even where pesticides and habitat loss are absent. Globally, terrestrial insect populations are declining at approximately 9% per decade, undermining pollination, decomposition, and the food chains that sustain birds, bats, and freshwater fish.

Tropical deforestation reached record levels in 2024, with 6.7 million hectares of primary rainforest destroyed — an 80% increase over 2023, according to the World Resources Institute. That rate equates to 18 football fields of ancient forest lost every minute. Wildfire became the largest driver of tropical forest loss for the first time. The first-ever Global Tree Assessment (October 2024) found that 38% of all tree species worldwide are threatened with extinction — more than double all threatened mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians combined.

These crises are not separate. They are strands of the same web that Pixcellence explores across its climate change and biodiversity educational content. The reef needs the forest. The forest needs the insect. The insect needs the climate. Pull one strand and the whole web trembles.

| Indicator | Measure | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global wildlife decline | 73% since 1970 | WWF LPR 2024 |

| Species threatened | 47,187 | IUCN Red List 2025 |

| Coral reefs bleached | 84% of global reefs | ICRI 2025 |

| Tropical forest loss (2024) | 6.7 million hectares | WRI 2025 |

| UK species at risk | 1 in 6 | State of Nature 2023 |

Species We Lost in 2024–2025 and Those on the Brink

The slender-billed curlew was officially declared extinct in November 2024 — the first documented bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa, and West Asia. Last reliably sighted in Morocco in 1995, its loss represents the permanent silencing of a species that once migrated across the entire Mediterranean basin. In the United States, the Key Largo tree cactus became the first documented local extinction caused by rising sea levels, having thrived as recently as 2021 before encroaching salt water destroyed its habitat entirely.

The scale of species at risk is immense. The IUCN Red List (updated April 2025) now tracks 169,420 species, of which 47,187 are classified as threatened. Among these, 10,443 species are critically endangered, with more than 1,500 having fewer than 50 mature individuals remaining in the wild. A July 2025 study published in Current Biology found that more than 10,000 species require urgent, targeted conservation intervention within the next decade to avoid irreversible decline.

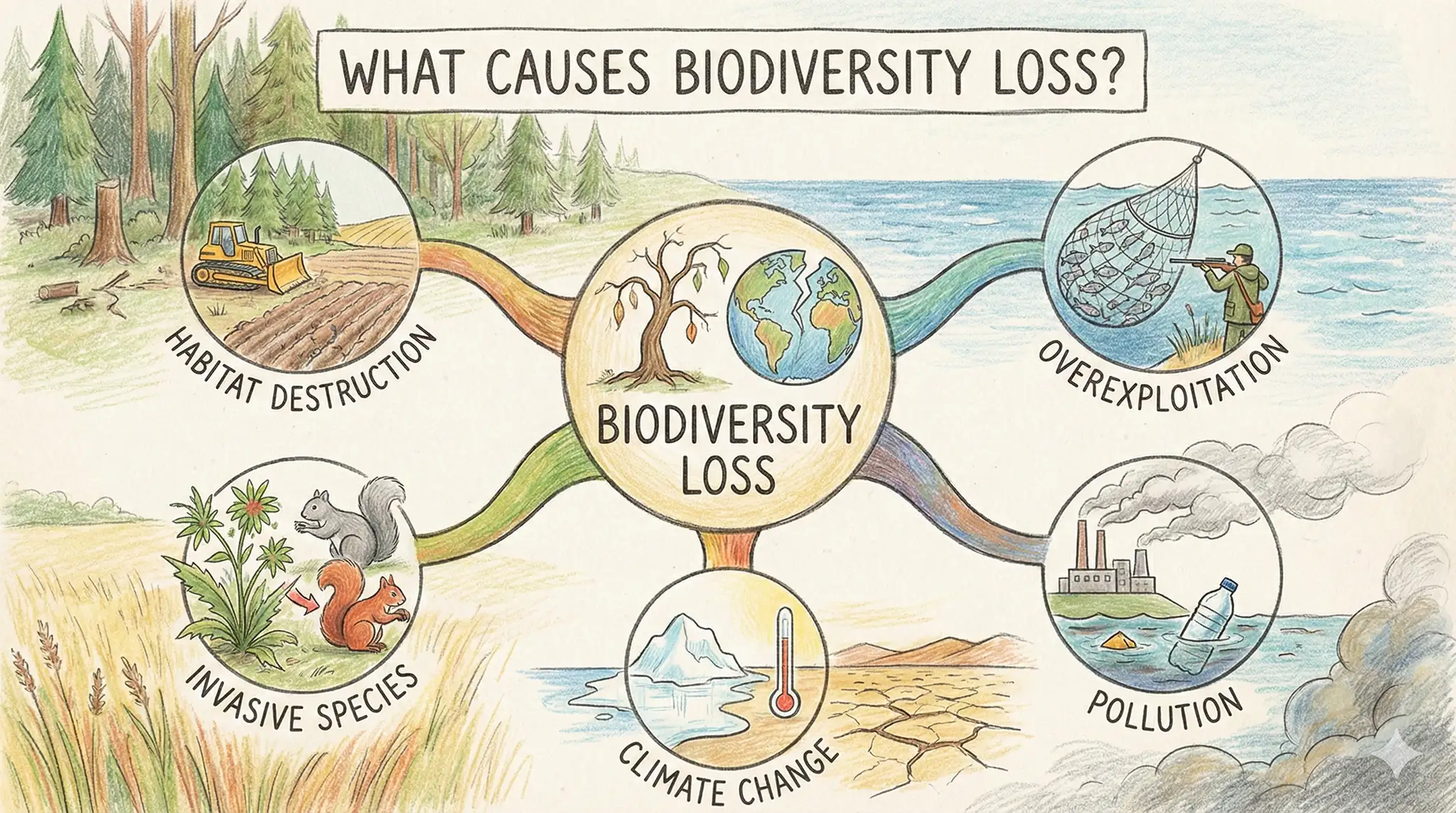

Each extinction is permanent. Each represents millions of years of evolutionary adaptation — what biologists call “deep time” and poets call irreplaceable beauty. Pixcellence’s human impact on biodiversity resources documents the five primary drivers: habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, invasive species, and climate change.

The Sixth Mass Extinction Debate: What Scientists Actually Say

The question of whether Earth is experiencing a “sixth mass extinction” is more nuanced than headlines suggest. A major 2023 study in Biological Reviews found that 48% of 70,000 monitored species are experiencing population declines, compared with just 3% increasing. Researchers Ceballos and Ehrlich have argued forcefully that Earth has entered a sixth mass extinction event, pointing to extinction rates running 100 to 1,000 times above background levels.

However, a February 2025 study by Wiens and Saban in Trends in Ecology & Evolution analysed 163,000 species and found that fewer than 2% of mammal genera and fewer than 0.5% of all genera have gone extinct in the past 500 years — “nowhere close” to the 75% threshold that has defined past mass extinctions. Their argument is not that the crisis is overstated, but that the technical term “mass extinction” requires a specific threshold of genus-level loss that has not yet been reached.

The scientific consensus, as synthesised by Pixcellence across its biodiversity collapse coverage, holds that biodiversity loss is catastrophic, accelerating, and unprecedented in human history — regardless of whether it technically meets the palaeontological definition of mass extinction. The practical distinction matters little to the species already gone.

Conservation Successes That Prove Recovery Is Possible

Against the gravity of these losses, genuine conservation successes demonstrate that decline is not destiny. The Iberian lynx — once the most endangered cat on Earth with fewer than 100 individuals remaining in 2002 — was reclassified from Endangered to Vulnerable by the IUCN in 2024 after two decades of intensive habitat restoration, captive breeding, and prey management. It is among the most celebrated conservation comebacks in history.

In October 2024, the largest dam removal in United States history was completed on the Klamath River, with four dams demolished and hundreds of miles of tributaries reopened. Within weeks, Chinook salmon were observed spawning in the river’s upper reaches for the first time in over a century — a powerful demonstration that ecosystems retain the capacity to heal when barriers are removed. The red-cockaded woodpecker has rebounded from 1,470 nest clusters to over 7,800. Green sea turtles have increased roughly 30% since the 1970s, with Florida nesting growing from approximately 4,000 females to over 230,000 nests.

In the UK, beavers received a clear legal path to wild reintroduction in February 2025. The Knepp Estate rewilding project in West Sussex has seen nightingales, turtle doves, and purple emperor butterflies return to 1,400 hectares of former failed farmland. European bison now roam the Wilder Blean project in Kent as ecosystem engineers. Pixcellence’s conservation of biodiversity resources documents these recoveries not as exceptions but as proof of principle.

“Every lynx returned from dread, and every river freed from bed, declares what yet the world may be.”

— Songs of the Living World, Pixcellence 2026

COP16, UK Biodiversity Net Gain, and the Policy Landscape

COP16 in Cali, Colombia (October–November 2024) — the largest biodiversity COP ever convened — achieved several landmark outcomes. The “Cali Fund” established a mechanism for sharing profits from digital genetic sequence data. A permanent subsidiary body was created for Indigenous Peoples and local communities, recognising their role as biodiversity stewards. A biodiversity-health action plan was adopted linking ecosystem degradation to human disease risk.

However, the conference ended in partial collapse when quorum was lost before all agenda items were resolved. Finance remained the critical failure: pledges fell far short of the estimated $200 billion needed annually to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. The resumed session in Rome (February 2025) adopted a resource mobilisation strategy and finalised the monitoring framework for the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Currently, approximately 17.6% of land and 8–10% of ocean is under some form of protection — far below the 30x30 target of 30% coverage by 2030.

In the UK, Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) became mandatory for major developments in February 2024, requiring a minimum 10% net gain in biodiversity as measured by Defra’s biodiversity metric. Pixcellence’s Biodiversity Net Gain explained resource details how this landmark policy works. However, in December 2025 the government proposed raising the small-site threshold, potentially exempting roughly 60% of planning applications from the requirement — a move conservation organisations including The Wildlife Trusts have strongly opposed.

Why Poetry Matters in a Crisis of Numbers

Science tells us how many species are declining. Poetry tells us why it matters that they exist at all. The biodiversity crisis is, at its root, a crisis of perception — what William Blake called “single vision and Newton’s sleep,” the reduction of a living world to raw material. A forest becomes timber yield. A meadow becomes development potential. A reef becomes an economic externality. We count what we have lost only after we have ceased to see what it was.

Pixcellence exists at this intersection of knowledge and feeling. The platform’s creative biodiversity resources — including original poetry, wildlife photography, and visual storytelling — are grounded in the belief that conservation requires both data and wonder. A child who encounters the statistic “73% decline” may forget it. A child who reads a poem about a world where the meadow falls silent carries something different — a sense of moral responsibility that no dataset alone can produce.

Blake understood this two centuries before the IPBES existed. He understood that the robin in the cage and the starving dog were not metaphors but moral facts — that cruelty to one living thing ripples outward through the entire fabric of creation. The ecological science of 2025 has simply confirmed, with extraordinary precision, what the visionary poet already knew.

What Can Individuals Do to Help Protect Biodiversity?

Individual action on biodiversity loss is both meaningful and necessary, particularly when multiplied across communities. Practical steps include transforming garden spaces by reducing mowing frequency — allowing wildflowers to establish supports pollinators directly. Planting native species, creating log piles for invertebrates, and installing water features for amphibians creates habitat corridors that connect fragmented ecosystems even in urban areas.

Supporting conservation organisations through donations, volunteering, or citizen science programmes amplifies individual impact. The UK’s Big Butterfly Count, RSPB Garden Birdwatch, and iNaturalist platform allow anyone to contribute monitoring data that directly informs conservation policy. Reducing consumption of products linked to deforestation — particularly palm oil, soy, and unsustainably sourced timber — addresses the economic drivers of habitat loss at their source.

Perhaps most importantly, individuals can use their voices. Writing to elected representatives about biodiversity policy, supporting the 30x30 target, and advocating for strong implementation of Biodiversity Net Gain legislation creates the political conditions for systemic change. Pixcellence’s practical guide to protecting biodiversity provides a comprehensive framework for turning awareness into sustained conservation action.

Frequently Asked Questions About the State of Biodiversity

How much wildlife has been lost globally since 1970?

Monitored wildlife populations have declined by 73% on average between 1970 and 2020, according to the WWF Living Planet Report 2024. Freshwater species have suffered most severely with an 85% decline, followed by terrestrial species at 69% and marine species at 56%.

How many species are currently threatened with extinction?

The IUCN Red List (April 2025) classifies 47,187 species as threatened out of 169,420 assessed, including 10,443 critically endangered species. The IPBES estimates approximately one million plant and animal species face extinction within the coming decades.

Is the UK really one of the most nature-depleted countries?

Yes. The UK retains less than half of its original biodiversity and one in six assessed species is at risk of being lost. Average species abundance has declined 19% since 1970, with 54% of flowering plants and 80% of butterflies experiencing significant declines.

What is the fourth global coral bleaching event?

The fourth global coral bleaching event (2023–2025) is the most extensive ever recorded, affecting 84% of the world’s reef ecosystems across 82 countries. Scientists warn that warm-water coral reefs have already crossed a critical tipping point at current warming levels of 1.4°C.

Are there any biodiversity conservation success stories?

Yes. The Iberian lynx was reclassified from Endangered in 2024 after a two-decade recovery programme. The Klamath River dam removal in the US enabled salmon to return after a century. UK beaver reintroduction legislation passed in 2025, and rewilding projects like the Knepp Estate demonstrate ecosystem recovery is possible.

What is the 30x30 biodiversity target?

The 30x30 target, adopted under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, aims to protect 30% of Earth’s land and ocean by 2030. Currently approximately 17.6% of land and 8–10% of ocean is under some form of protection, meaning significant expansion is required within five years.

The Web Still Holds: A Conclusion

The state of biodiversity in 2025 is dire by any honest measure. A 73% decline in wildlife, one million species at risk, 84% of reefs bleached, 18 football fields of rainforest lost every minute, and the UK ranking among the most nature-depleted nations on Earth. The curlew’s call has been silenced for ever. The insect hum is fading from even the most pristine places on Earth.

And yet. The lynx stalks the Iberian hills again. Salmon surge through the Klamath for the first time in a century. Beavers are building in English rivers. The web of life, though frayed, still holds — and everywhere that human beings have chosen restoration over extraction, it has begun to mend.

Blake wrote that we hold infinity in the palm of our hand. That is not mysticism. It is ecology. Every species lost diminishes the whole. Every species saved sustains it. The question now — the only question that matters — is whether we will choose to be the generation that let the web fall, or the generation that wove it whole again.

Discover. Learn. Protect.

Pixcellence is committed to making biodiversity education accessible, engaging, and actionable for everyone who cares about protecting the natural world.

Explore the Biodiversity Education Hub →